Copper (Cu) bioavailability for ruminants is mainly determined by sulfur, molybdenum and iron levels in the diet. Thus, complete forage analyses are essential to fine tune the quantity of Cu needed to meet the animal requirements, without forgetting drinking water which can be a significant source of iron and sulfur for the animal.

Product Manager

Animine

COPPER: ESSENTIAL FOR RUMINANTS

It has long been recognized that copper (Cu) is an essential trace element in ruminants. As it is required in many key enzymes, any sub-clinical deficiency will impair animal health, fertility and production performance.

Cu requirements and maximum Cu level authorized in the European Union are presented in Figure 1. For bovine, the requirements are around 10 mg/kg DM with higher values for dairy cows in the close-up period and in the first weeks after parturition. Following the 8th revised edition of the Nutrient Requirement of Dairy Cattle (NASEM 2021) little change is observed in requirements in Cu for average lactating cows (11 mg/kg DM). However, for dry cows, requirements increased 40% (17 mg/kg DM) while for high producing cows, requirements decreased 45% (9 mg/kg DM).

Higher values are recommended for caprine (up to 25 mg/kg DM) but lower for ovine (up to 10 mg/kg DM) which are highly sensitive to excess Cu. A genetic variation observed in Cu absorption can also influence Cu requirements. Literature mentions in particular higher requirements in Scottish Blackface than in Texel sheeps and in Jersey than in Holstein Friesians cows.

![]() LIMITATIONS OF REQUIREMENTS SYSTEM

LIMITATIONS OF REQUIREMENTS SYSTEM

With the most recent research on dairy cattle mineral nutrition, guidelines are becoming more and more accurate in defining dietary requirements. Still, some limitations in the system do exist. Those requirements systems do not take into account rumen effect, ‘non absorbed’ effects or antagonistic effect. That’s why adjustments need to be done despite the high precision of the latest data.

Because of the small margin between Cu deficiency and Cu toxicity and because the high susceptibility of Cu to bind antagonists in the rumen, Cu is a good example of an element to adjust closely in ruminants.

RISK OF SECONDARY DEFICIENCY

Secondary deficiency happens when even at proper level of Cu supplementation, the presence of other dietary factors interferes with mineral absorption and metabolism. This phenomenon is the main cause of Cu deficiency in ruminants. Sulfur (S), molybdenum (Mo) and iron (Fe) are the most important dietary factors to negatively impact Cu absorption.

The signs of Cu deficiency vary from mild symptoms such as loss of coat condition and poor growth, to more severe symptoms like infertility and diarrhea.

As forage and diet compositions are seasonal and variable from farm to farm, secondary deficiencies are difficult to predict. Therefore, Cu in ruminant diets is usually supplemented well above nutritional requirements, to guarantee Cu absorption regardless of the presence of antagonists.

OVERSUPPLY IN DAIRY CATTLE

While in the past Cu deficiencies used to occur in grazing ruminants, researchers have observed in a growing number of countries in Europe, America and Oceania, an increased concentration of Cu in the liver of dairy cow herds over the years.

(Image courtesy by Dr. Clarkson)

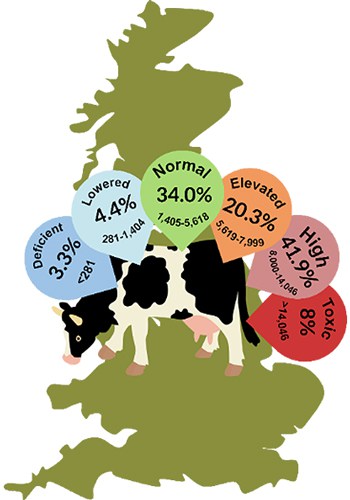

A study carried out at the University of Nottingham (UK), showed that most sheep (60%) have normal liver Cu and are more likely to be deficient. The same study showed that 70% of dairy cattle in the UK have high Cu status (Figure 2) with 60% of the farms feeding animals with Cu levels above 20 mg/kg DM and 8% above the legal limit.

The main reasons reported were misinformation of farmers and the fear of deficiency. In addition, the multichannel supply of trace elements (via concentrates, mineral feeds, nutritional supplements…) and the variability in forages composition make it difficult to monitor total Cu supplementation.

CHRONIC COPPER TOXICITY

Prolonged Cu intake, above requirements, can lead to chronic toxicity which is the result of the slow accumulation of Cu in the liver during a long period of time. At the opposite of acute toxicity, Chronic Copper Poisoning can remain ‘silent’ for months or years, before the toxicity is apparent.

The elevation of liver enzymes in the blood, that indicates hepatopathy caused by high levels of Cu, can be related to a wide range of other diseases. Additionally, clinical signs are mild and with low morbidity which can often be overseen by veterinarians.

Increase in blood Cu is only seen as a second stage when the liver is overloaded and Cu is released into the bloodstream. This causes acute toxicity with animals often dying within 24-48h.

A growing number of lethal cases reported by veterinarians showed that such silent intoxication is spreading in dairy herds, which urges the development of strategies to monitor herd Cu status and amplify the awareness of farmers for Cu toxicity.

Recent research indicates that Cu already accumulates in bovine liver at dietary levels recommended by the industry, and that cattle could be less tolerant to Cu than previously thought.

CONCLUSION

This topic highlights the importance of precision mineral feeding in order to guarantee an efficient supply of Cu, safe for the animal and for the environment.

Cu bioavailability for ruminants is mainly determined by sulfur, molybdenum and iron levels in the diet. Thus, complete forage analyses are essential to fine tune the quantity of Cu needed to meet the animal requirements, without forgetting drinking water which can be a significant source of iron and sulfur for the animal.

The choice of the source of copper supplemented in the feed is also of importance. Indeed, Cu sources with known physicochemical characteristics and dissolution kinetics can help to select the one which is the less susceptible to form complexes in the rumen. Monovalent copper oxide, combines high bioavailability with a low solubility at rumen pH. This innovative source of Cu will help to restrict the need for higher Cu dosages in ruminant diets and to preserve animal productivity, health and welfare.