Soybeans demand vast amounts of land and water, and their cultivation often relies on intensive monoculture farming that depletes soils and reduces biodiversity. Prices of soybeans and fishmeal have also soared, leaving farmers paying far more to raise animals to market size. For farmers in developing countries in particular, this volatility makes traditional feed sources increasingly unaffordable and unsustainable.

Senior Researcher

International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

In a village in Kisumu County, Kenya, chicken farmers have found an unlikely ally: Flies and their squirmy larvae. At first, one farmer wouldn’t dare touch the wriggling critters as they devoured piles of organic waste. She was frightened by their appearance. But that fear quickly faded once she discovered how useful they were—not only harmless, but a healthy, affordable feed for her chickens. “Even the chickens love them,” she says with a smile. “They eat them at a high speed.”

A FOOD SYSTEM UNDER STRAIN

Her experience speaks to a much bigger story. Food systems around the world are under strain. Farmers face rising costs for fertilizer and animal feed. Land and water are becoming scarcer. At the same time, unsustainable farming practices and heavy use of chemicals are degrading soils, harming biodiversity, and polluting water. Food loss and waste occur across the entire value chain, with some estimates suggesting that almost 30% of food produced never reaches consumers. This waste generates billions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year. Meanwhile, the global population is growing, and demand for meat, milk, and fish is expected to rise by up to 70% by 2050—with much of this heightened demand expected to be in developing countries. This places even greater pressure on feed supplies and makes finding sustainable, affordable solutions more urgent than ever. The humble black soldier fly is emerging as an innovative, circular solution that can help solve many of these challenges by turning waste into food security.

Soybeans and fishmeal are major protein sources for animal feed production. Around 85% of the world’s soybeans are processed into animal feed, while more than 20% of all fish caught globally are processed into fishmeal for pigs, poultry, cattle, and farmed fish. This is becoming increasingly unsustainable. Soybeans demand vast amounts of land and water, and their cultivation often relies on intensive monoculture farming that depletes soils and reduces biodiversity. Prices of soybeans and fishmeal have also soared, leaving farmers paying far more to raise animals to market size. For farmers in developing countries in particular, this volatility makes traditional feed sources increasingly unaffordable and unsustainable.

TURNING WASTE INTO FEED

Black soldier fly (BSF) farming is a promising alternative. It’s a low-cost, environmentally friendly source of protein at a time when farmers are confronted with rising feed and agricultural input prices. The larvae’s protein content rivals or even surpasses the traditional sources like fishmeal and soybeans. The BSF larvae can cope with a wide range of environmental conditions and the adult fly does not spread disease.

What makes BSF especially powerful is its ability to turn waste into value using low-cost technologies, which can be produced on-farm or near farming communities. The larvae can feed on a wide variety of organic materials, including food scraps and market waste which are produced in huge volumes in urban and peri-urban areas. As they consume this waste, the larvae grow into protein-rich biomass while leaving behind a nutrient-rich residue. The larvae can then be processed into feed for poultry, fish, and pigs, while the residue serves as a valuable soil conditioner.

This adaptability and dual benefit—reducing waste while producing affordable animal feed—makes BSF one of the most promising circular solutions for developing countries. It tackles two urgent challenges at once: the rising cost of animal feed and the mounting problem of organic waste.

CAN BSF FARMING PAY OFF?

Insights from Kenya’s BSF Enterprises

Across Kenya, a quiet insect revolution is taking shape. From Kirinyaga to Nakuru, 14 BSF enterprises are proving that BSF farming can be both profitable and sustainable. These insights come from a financial feasibility study conducted by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) under CGIAR’s Multifunctional Landscape (MFL) Science Program, which analyzed BSF operations across five counties in central, eastern, and Rift Valley Kenya.

The enterprises vary in scale—small and medium producers process under 15 tonnes of waste a year, while large-scale farms handle up to 700 tonnes. Yet all share a common goal: transforming organic waste into high-value animal feed and fertilizer.

From Waste to Value

Most enterprises rely on locally available organic waste—market waste, kitchen leftovers, and vegetable farm residues—used by nearly two-thirds of the surveyed farms. Others source from slaughterhouses and hotels. The BSF larvae feed on this waste, reducing its volume while producing nutrient-rich protein and frass (Figure 1).

Larger farms benefit from economies of scale. The IWMI study found that while small and medium enterprises invested about 17 Kenyan shillings (Ksh), or US$ 0.16 per kilogram of waste treated, large-scale ones managed at Ksh 9.76 (US$ 0.09) per kilogram. Most rely on simple, low-tech setups—manual sorting, basic tools, and often family-owned land. This keeps start-up costs relatively low.

Profits in the Process

Despite modest infrastructure, BSF farms in Kenya are turning solid profits. Labor makes up the bulk of operational costs (63–96%) due to the manual nature of processing, but gross margins often exceed 70%, regardless of scale.

Enterprises generate income from several BSF products:

• Eggs – sold at up to Ksh 200,000 (US$ 1,625) per kilogram to new BSF producers.

• Larvae – a protein-rich animal feed ingredient sold for Ksh 150–250 (US$ 1.2–2) per kilogram.

• Frass – the nutrient-rich residue used as fertilizer, sold for Ksh 50–60 (US$ 0.40 – 0.49) per kilogram.

Many enterprises also diversify by offering training and starter kits to aspiring BSF farmers, creating both additional income and local capacity. Training sessions cost between Ksh 1,000 and 2,500 (US$ 8–20) per person, attracting up to 200 participants each year.

A YOUTH STORY: FROM CHURCH WALLS TO CIRCULAR ECONOMY

One such enterprise is AderoFarms Karateng’ Ltd., a youth-led agribusiness in Kisumu County. Founder Christopher Adero Okeyo said, “We began inside an incomplete church building, not because it was ideal—but because it was all we had. At the time, we couldn’t afford the expensive BSF infrastructure. What we did have was a dream: to build a circular economy model that turns waste into value and empowers communities.”

Today, AderoFarms processes over 4 tonnes of food waste weekly, collected from local markets and hotels. Since 2024, the enterprise trained more than 1,300 farmers—with a strong focus on youth, women, and persons with disabilities—on BSF farming and entrepreneurship. Their products include BSF eggs (US$ 0.32) per gram for companies managing waste in hotels and parks, larvae (US$ 2.8) per pack for community farmers, pupae (US$ 7.2) per kilogram for startup BSF farms, and frass (US$ 0.4) per kilogram for vegetable growers and nurseries.

RISKS FACED BY BSF ENTERPRISES

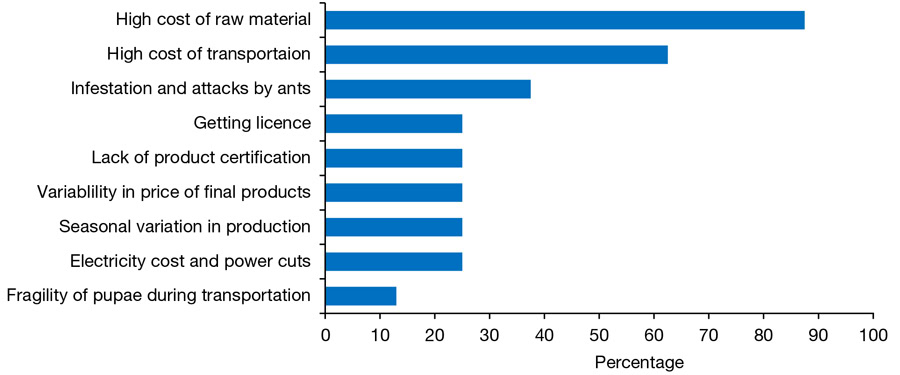

The IWMI study also highlighted key risks. Rising competition for organic waste was cited by 88% of enterprises, while transportation costs—especially for fragile pupae—were a concern for over 60%. Infestations by houseflies and ants, limited product certification, and market monopolization by a few large players pose additional challenges. Some farmers also hesitate to adopt BSF products, confusing the larvae with housefly maggots or underestimating the value of frass as fertilizer (Figure 2).

FROM FEASIBILITY TO COMMUNITY INNOVATION

Building on the feasibility study findings, IWMI, in collaboration with Kisumu community, established a community-run BSF plant that processes up to 40 tons of organic waste annually. Operating since 2024, the plant doubles as a training hub for over 100 farmers, turning organic waste into high-quality feed and fertilizer. The initiative exemplifies how science-based insights can evolve into community-driven circular economy solutions. Dr. Noah Adamtey, Senior Researcher and Resource Recovery Expert at IWMI, describes BSF as “environmental engineers” whose benefits span food, nutrition, and even pharmaceutical applications.

BUILDING A CIRCULAR FUTURE

From small youth-led startups to community-scale models, BSF farming in Kenya is proving both financially viable and socially transformative. With continued investment, knowledge sharing, and supportive policies, the humble BSF could become a cornerstone of sustainable, circular agri-food systems across Africa.

About Dr. Solomie Gebrezgabher

With over ten years of experience in research and project implementation focused on advancing circular bioeconomy solutions for economic, social, and environmental sustainability in developing countries, Dr. Solomie Gebrezgabher’s work focuses on the economics of resource recovery, business model innovation, and entrepreneurship in circular systems. She has led and contributed to numerous projects across multiple countries, driving research, capacity building, and the scaling of circular bioeconomy solutions in diverse contexts.