Thermal stress in cows disrupts the delicate balance between heat production and dissipation, leading to a cascade of physiological effects that impact digestion, immunity, and reproduction. While cows are efficient feed-to-food converters, their limited ability to sweat makes them vulnerable in hot, humid conditions. As climate challenges rise, innovative solutions are being explored to safeguard performance and welfare—especially outside the thermoneutral zone.

Veterinarian

Biochem

Cows have superpowers. Humans and cows share a long history, with humans relying on these animals for a stable food source. The symbiotic relationship between cows and their ruminal microorganisms is crucial to produce highly nutritious food from poor-quality feed—using plants, stems, and by-products that are unsuitable for other production animals. Consequently, they play a substantial role as a valuable source of food.

A 4-LEGGED HEATING POWER STATION

The cow is a so-called homeothermic animal. That is, they can maintain their body temperature through metabolic activity. With a constantly active metabolism, cows are excellent feed-to-food converters. However, these superpowers come at a cost; they generate an incredible amount of heat. In an adult cow, this can be almost 1.2 kWh of heat, enough to theoretically heat a small house with the excess heat from three cows. A fact that has been exploited by farmers for centuries.

A cow’s metabolism is a complex interplay of microbial activity and physiological efficiency, which generates heat from basal metabolism, activity, digestion, and production. Basal metabolic heat comes from basic cell functions that keep the body alive. It also comes from muscle activity, and from the heat produced by other bodily processes that help with growth, lactation, pregnancy, and the production of proteins or fats.

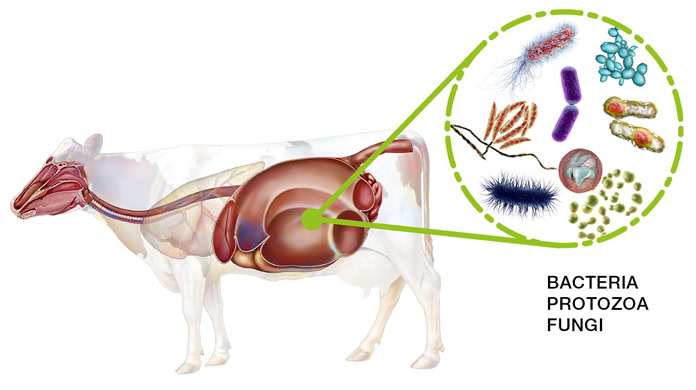

The digestion of feedstuffs also releases heat. At the center of digestion is the rumen—a large-volume anaerobic bioreactor system containing billions of bacteria, protozoa, and fungi—and much of the heat generated is from the intense microbial activity here (Figure 1). Ruminal fermentation generates enough heat to raise the rumen temperature to about 1° C higher than the core body temperature of 38 – 39° C.

These microorganisms in the rumen break down carbohydrates from the diet fermentation into volatile fatty acids (VFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These VFAs are absorbed through the rumen wall and are used by the cow as a primary source of energy, generating more heat through processing, particularly during gluconeogenesis in the liver. This makes the cow a true “thermal power station on four legs.”

WHEN SUPERPOWERS FAIL

Although a biomechanical masterpiece, the dairy cow is vulnerable to high ambient temperatures. As soon as the temperature rises, her finely tuned balance of heat production and loss is disrupted, and the consequences can be severe. Heat stress—the invisible kryptonite of dairy cows worldwide—has a significant impact on their health, welfare, and production.

Thermoregulation is the process of maintaining core body temperature within a narrow range and is thought to optimize organ and system function. Homotherms, such as cows, control the exchange of heat between their body and the environment so that the heat gained from metabolism is balanced by the heat lost to the environment (Figure 2). In this way, body temperature remains stable.

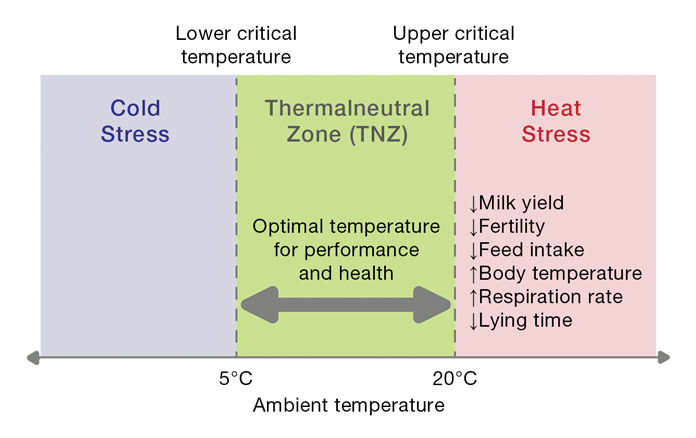

The relationship between core body temperature and the temperature of the environment can be described in terms of several zones that distinguish different physiological responses. The narrowest zone is the thermoneutral zone (TNZ).

This zone describes the cow’s comfort zone. Within the thermoneutral zone, they do not need to expend additional energy to keep their body temperature stable: heat production and heat loss are in a harmonious balance.

On either side of the TNZ is the temperature range at which heat balance can be achieved, but the metabolic rate or evaporative heat loss will change to maintain balance. In this range, metabolic rate increases at low temperatures and evaporative cooling increases at high temperatures. As such, a homeotherm is under thermal stress whenever it is outside of its TNZ. A dairy cow’s TNZ is between approximately 5 – 20° C (Figure 3) although when lactating, they can withstand lower temperatures.

Conduction, convection, radiation, and evaporation are just some of the ways cattle can dissipate heat. The difference between a cattle’s body temperature and the ambient temperature determines the success of these techniques and can quickly reach its limits (Figure 4). When the outside temperature rises in combination with high humidity, thermal stress in cows often reaches critical levels as evaporation becomes negligible.

Exposure to temperatures just above TNZ causes an adjustment in heat transfer by increasing blood flow to the skin. This increases the removal of metabolic heat to the periphery where it is lost. However, when the ambient temperature exceeds the skin surface temperature (~ 36° C), heat is transferred from the warmer air to the cooler skin, adding to body heat. To maintain thermal balance, evaporative cooling—through sweating and panting—must increase to match the additional heat load.

Unlike more heat tolerant animals like horses, cows only have about 800 sweat glands per cm². As a result, cows sweat inefficiently and rely more on increased respiration for evaporative cooling, increasing from 40 – 60 breaths per minute to over 100 breaths per minute. The onset of panting impacts the cow’s acid/base balance and can lead to respiratory alkalosis. At the same time, water requirements increase dramatically—heat stressed cows have increased water requirements of up to 200 liters per day.

![]() CONSEQUENCES OF HEAT STRESS

CONSEQUENCES OF HEAT STRESS

When heat dissipation is no longer sufficient, physiological adaptation mechanisms kick in. The cow reduces feed intake as microbial fermentation in the rumen generates additional heat leading to a cascade of physiological responses (Figure 5). As blood distribution is diverted to the skin to dissipate heat, blood flow to organs such as the rumen and liver is reduced, further compromising digestive efficiency and metabolic processes. This can lead to reduced energy supply, increased oxidative stress, mobilization of body reserves, hormonal imbalances and reduced milk yield. Immune defenses are also compromised, making animals more susceptible to infection and inflammation.

The negative effects of heat stress on dairy cattle are well documented. In addition to reduced health and performance, the reproduction and fertility of dairy cows are severely affected, affecting the next generation. The fertility of a dairy cow is influenced by many factors, but environmental factors appear to be the most important.

Heat stress can alter estrus duration, uterine function, endocrine status, and follicular growth and development. Prolonged heat stress may also affect early embryonic development and survival, fetal growth, and colostrum quality. In addition, conception rates in dairy cows are negatively affected by extended periods of heat stress, resulting in longer calving intervals.

Conception rates in high yielding dairy cows have been declining—often attributed to physiological changes, management changes and increased milk production. However, during periods of heat stress, conception rates decrease even further compared to periods without heat stress. One study found up to a 23% decrease in conception rate for heat stressed cows compared to non-heat stressed cows, and another found that body temperatures > 39.1° C caused conception rates to drop from 21% to 15%. Finally, a third study found that exposure to heat stress 3 weeks prior to artificial insemination can negatively affect conception rates. Only in the TNZ can dairy cows reach their full genetic potential at the lowest physiological cost and highest productivity.

COUNTERACTING THE EFFECTS OF A COW’S KRYPTONITE

There are several different approaches to significantly reduce the pressure of heat stress on cows. They all have the same goal: How can I get my herd to suffer fewer losses and less health stress during hot periods? These approaches range from housing conditions, such as the correct placement, orientation, and strength of fans and spray systems, to management with adapted feeding times, to our specialty: Feed technology.

We are researching innovative approaches, including the use of phytogenic additives, to support the cow’s natural metabolic processes and sustainably reduce heat stress. Our results so far are very promising—stay tuned for this exciting new solution. Let’s take on this challenge together!

About Dr. Melinda Culver

A veterinarian with a strong interest in animal health and nutrition, Dr. Melinda Culver earned her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree in 2004. She pursued a Ph.D. in Animal Science at Washington State University (2006), focusing on muscle and fat cell development. Dr. Culver transitioned from veterinary practice to the supplement industry, where she’s spent over 15 years using her knowledge to improve animal and human well-being through advancements in nutrition. She joined Biochem in 2022, bringing her extensive experience to the team.