Producers try to overcome the low voluntary intake immediately after weaning by enhancing feed palatability. While this strategy may effectively increase feed consumption, the status of the intestine prevents an effective nutrient digestion, and contribute to exacerbating oxidative stress. This is worrisome because weight gain is a direct consequence of intake, and low gains at this stage may either cause lower weight at the end of fattening, or unnecessarily lengthening the time required to reach market weight. In both cases economic losses are incurred by the producer.

Senior Nutrition Scientist

Layn Natural Ingredients

It is customary in modern intensive swine production the use of early weaning techniques to improve productivity. This, however, causes an intense oxidative stress to the piglet due to the sudden separation from the sow, the rapid change in the diet, and the change of physical and social environment. Affecting chiefly the intestine, it results in perturbations of physiological and biochemical functions, nutrient digestion and absorption, mucosal immune function, the onset of intestinal inflammation, and changes in intestinal microbiota. The ultimate consequences are decreased feed intake, occurrence of postweaning diarrhea (PWD), and growth rate restriction.

The main characteristics of a healthy gut include: a healthy proliferation of epithelial cells lining the intestinal wall; proper gut barrier function; a beneficial and balanced gut microbiota; and a well-developed intestinal mucosa immunity, which is not the case in early weaned piglets.

That is because the piglet’s intestine at this stage is not mature and its digestive and immune systems have not had enough time to evolve, causing the piglets to poorly adapt to the complex weaning environment. Physiological immaturity also means insufficient secretion of digestive enzymes, which makes solid feed digestion difficult and reduces voluntary feed intake.

Poor nutrient flow leads to oxidative stress by exhausting the antioxidant enzyme equipment and increasing production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS – superoxide and hydrogen peroxide). When combined with hydrogen peroxide and iron through Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions, superoxide generates the hydroxyl radical. This free radical oxidizes the enterocyte membrane phospholipids, and may directly damage DNA, creating the conditions required for early cell death, and additionally stimulate specific cell pathways within the enterocyte, leading to processes detrimental to gut health and overall performance.

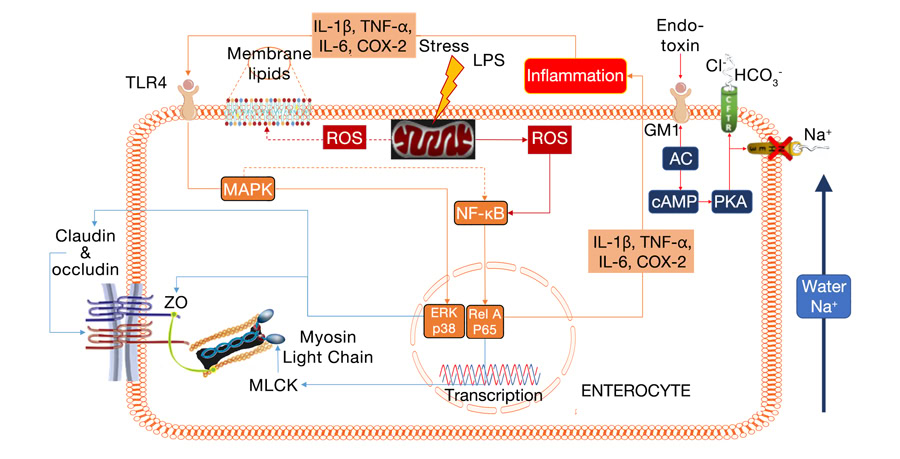

ROS build-up activates the Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway. This translocates to the cell’s nucleus and changes protein transcription. One effect is impairing the synthesis of tight junction proteins, altering the function of the intestinal barrier. This increases gut permeability and causes microbiota imbalances that favor intestinal colonization by entero-toxigenic Escherichia coli, leading to diarrhea. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide enhances ROS production by the mitochondrion, increasing oxidative status. Another effect is the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8), causing intestinal inflammation and altering local innate immunity.

The diagram contained in Figure 1 schematically summarizes the implications of the enhanced oxidative status in intestinal cells.

TLR4: toll -like receptor 4; NF-kB: Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells pathway; MAPK: Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase pathway; ERK, Rel A: nucleus-translocated components of pathways modifying protein transcription; MLCK: Myosin Light Chain Kinase; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; IL-1b, TNF-a, IL-6, COX-2: pro-inflammatory cytokines; GM1: ganglioside receptor of ETEC LT toxin; LPS: bacterial lipopolysaccharide.

Producers try to overcome the low voluntary intake immediately after weaning by enhancing feed palatability. While this strategy may effectively increase feed consumption, the status of the intestine prevents an effective nutrient digestion, and contribute to exacerbating oxidative stress. This is worrisome because weight gain is a direct consequence of intake, and low gains at this stage may either cause lower weight at the end of fattening, or unnecessarily lengthening the time required to reach market weight. In both cases economic losses are incurred by the producer.

So, the use of additives to enhance daily feed intake may have the intended consequence of aggravating the intestinal physio-metabolic status. It is in this complex technical and economic environment that polyphenol-rich botanical extracts find their role of restoring piglet’s homeostasis and functional balance.

There is extensive published research showcasing the ability of polyphenols to reduce the oxidative status of production animals, recovering the usual productive parameters as the outcome of their use. This is achieved because polyphenols operate at several levels within the cell of the target organ. In the present case, the target is the intestine and more specifically the enterocyte. The following paragraphs contain a descriptive mode of action of polyphenols in the intestinal environment.

Initially, polyphenols quench Reactive Oxygen Species (free radicals). If ROS build-up is the originating step of the issues involved in post-weaning stress, reducing the amount of radicals will diminish their impact on some cell components. The quenching of radicals preserves the antioxidant enzymatic system. There is less need of using catalase, superoxide dismutase o glutathione peroxidase to control free radicals, and less risk of exhausting them in highly oxidative situations.

Quenching of ROS also inhibit the activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways, thus protecting the intestinal barrier function, and decreasing the encoding of inflammatory cytokines.

In addition, polyphenols activate an oxidation protective pathway named Nfr2, that encodes new antioxidant enzymes such as heme oxygenase-1. These enzymes block the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines and help reducing the immunity disruption caused by them.

Other polyphenols collectively act upon E. coli associated diarrhea, either by preventing fimbriae adhesion to the enterocyte, or disrupting the adhesion of LT toxin to its ganglioside receptor in the cell membrane of the enterocyte. In both instances, the outcome is reduced intestine colonization by Escherichia coli, and substantial decrease of post-weaning diarrhea.

As a global leader of botanical extracts, Layn supplies the swine industry with high quality, polyphenol-rich extracts targeted to the specific issues that arise immediately after weaning. TruGro CGA is a powerful metabolic antioxidant recommended for high health swine units, where microbial diarrhea is not a pressing issue. Its focus is on reduction of oxidative stress and inflammation, modulating the local immunity and reinforcing the intestinal barrier. It favors the acceptance and digestion of early weaning feed, resulting in faster body weight gain.

On the other hand, TruGro PW targets E. coli diarrhea. While also reducing the oxidative stress, it prevents the adhesion of LT toxin to its receptor, avoiding water influx into the intestinal lumen, a major cause of diarrhea. Other polyphenols in its composition capture water, increasing the dry matter content of intestinal digesta and contributing to reducing diarrhea cases. Experimentation with TruGro PW has shown 60% to 80% reduction of diarrhea rate for the three first weeks of weaning.

TruGro CGA and PW are useful tools intended for an efficient and profitable piglet rearing.

About Juan Javierre

Senior Nutrition Scientist at Layn Natural Ingredients, Juan Javierre is a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, as well as a nutritionist and researcher. Javierre has over 30 years of experience in animal production in Europe, the Americas, Southeast Asia, and China.