Typical symptoms of pathogenic E. coli infection include diarrhea, omphalitis, pericarditis, aerosacculitis, as well as infected skin lesions (cellulitis) in broilers or genital tract infections in breeders, occurring by contiguity. These clinical signs not only impair bird welfare but also result in considerable performance losses in broiler, layer and breeder production. Environmental stressors, inadequate biosecurity, and compromised mucosal integrity or immune function further increase birds’ susceptibility to colibacillosis.

Poultry Technical Deployer

Lallemand Animal Nutrition

In modern poultry production systems, birds are particularly sensitive to inflammation caused by a late and inconsistent establishment of the microbiota, as well as numerous danger signals (e.g., high stocking density, genetics, vaccination, handling or transport). Chronic inflammation creates favorable conditions for the growth of opportunistic pathogens (i.e. E. coli), leading to bird morbidity and performance losses. Bird infection, whether bacterial, viral, or triggered by environmental stress, can occur unpredictably and is often triggered by inflammation. That’s why it is essential to adopt a broad proactive approach, applied to all flocks, one that mitigates risks before they develop into problems.

Colibacillosis remains one of the most impactful bacterial diseases in poultry farming worldwide, silently driving high mortality rates and major economic losses. Beyond its financial impact, colibacillosis raises serious concerns for animal welfare, making it a critical issue that poultry professionals cannot overlook.

Escherichia coli, a Gram-negative bacterium, is among the first enterobacteria to colonize the digestive tract within a few hours after hatching. As such, it is considered a commensal microorganism in the poultry gut. While most of Escherichia coli strains are harmless commensals, some strains such as Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) have acquired virulence factors that confer pathogenicity, leading to colibacillosis in chicks, broilers, laying hens, and breeders.

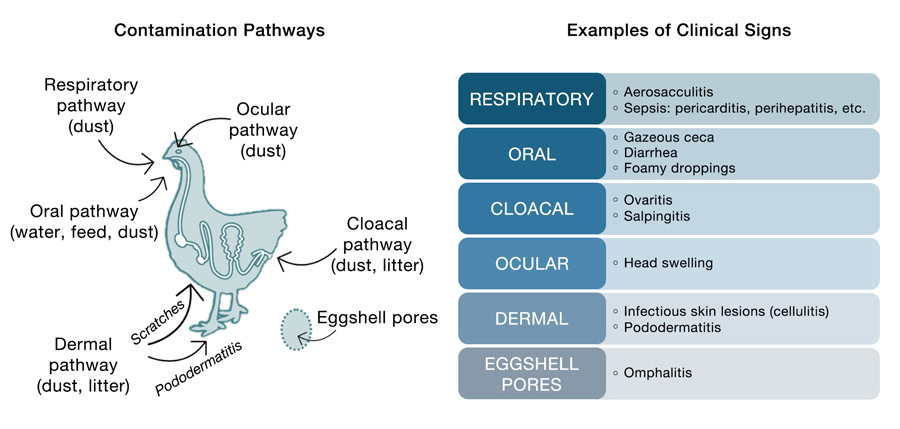

Typical symptoms of pathogenic E. coli infection include diarrhea, omphalitis, pericarditis, aerosacculitis, as well as infected skin lesions (cellulitis) in broilers or genital tract infections in breeders, occurring by contiguity. These clinical signs not only impair bird welfare but also result in considerable performance losses in broiler, layer and breeder production. Environmental stressors, inadequate biosecurity, and compromised mucosal integrity or immune function further increase birds’ susceptibility to colibacillosis.

E. coli contamination can occur at a very early stage, even during the egg phase. If breeding birds are infected, vertical transmission may occur either through the genital tract during egg formation, or via eggshell contamination, eggshell’s pores (30 µm) being permeable to bacteria such as E. coli (≈ 2–3 µm). In adult birds, contamination most commonly occurs via the respiratory route, through inhalation of contaminated dust. Water for drinking or feed can also serve as vectors of contamination. E. coli can cause localized infections, or may lead to septicemia after adhering to mucosal surfaces and entering the bloodstream. Within the intestinal tract, APEC initially adhere to enterocytes using their pili, then release exotoxins that trigger a strong inflammatory response, resulting in the symptoms previously described. However, even after death, APEC continue to release endotoxins, which are responsible for the symptoms of colibacillosis (Figure 1).

©Lallemand

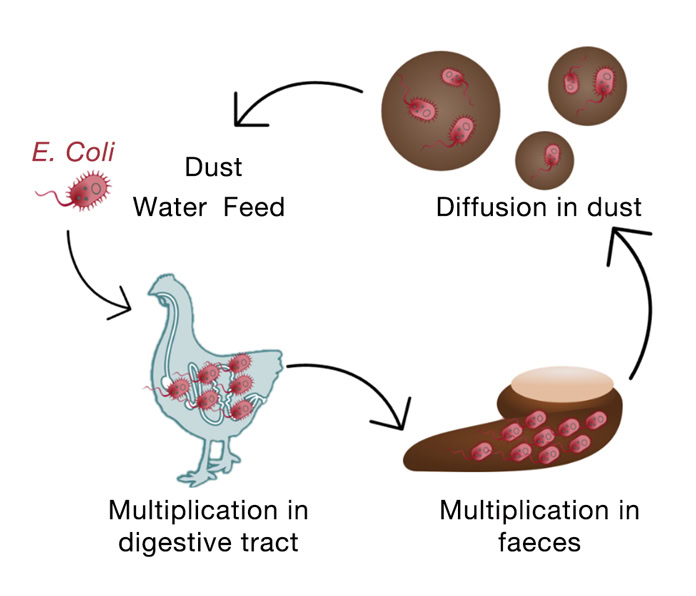

The infection spreads rapidly within a poultry flock and its housing environment, as birds act as effective E. coli “fermenters”. Infected birds excrete large quantities of E. coli in their feces, where the bacteria can multiply quickly. In confined environment, dust is mostly composed of suspended fecal particles (up to 95% of dust particles). As a result, pathogens excreted in droppings are dispersed throughout the environment (air, floors, walls, farming equipment) via dust, leading to widespread contamination of the flock through the gut, the respiratory tract, or even the cloaca (Figure 2).

Contamination with E. coli does not always lead to colibacillosis. However, the risk of serious disease increases when birds experience a drop in immunity -due to stress, viral infections, mycotoxins in feed, or other factors- combined with a weakened mucosal barrier (e.g., leaky gut, skin lesions, dusty environment, etc.) or excessive environmental pressure (e.g., inadequate sanitation, history of E. coli-related mortality, biosecurity breaches, poor drinking water quality, presence of pests, etc.). Stress triggers the amount of E. coli excreted in birds’ feces, resulting in a higher bacterial load. At the same time, weakened immunity creates favorable conditions for the development of colibacillosis. In modern poultry, which are particularly sensitive, each farming challenge can result in a colibacillosis outbreak within the flock, resulting in reduced performance and, in severe cases, mortality (Figure 3).

Mainstream approaches to managing colibacillosis in poultry – vaccines and antibiotics – face growing limitations. Autogenous vaccines require strain-specific formulations, with usually a combination of several valences tailored to the farm, and frequent updates to address emerging new E. coli strains within the flock. This strategy involves high direct costs and requires additional handling when vaccines are administered by injection. Antibiotic treatments typically result in a rapid drop in mortality, but these effects are often short-lived. Once treatment ends, the environment remains heavily contaminated, facilitating recontamination, and a rebound in mortality is often observed within a few days. Furthermore, repeated use of antibiotics promotes bacterial resistance to the active molecules used, limiting future treatment options. The range of available medication has been significantly reduced due to regulatory constraints on the use of colistin and some newer-generation antibiotics. The remaining options are less specific to E. coli, and the withdrawal period for egg marketing (sometimes up to 3 weeks post-treatment) makes their use economically challenging.

Nutrition has always been part of the toolbox to maintain animal health and welfare. This challenging context has accelerated the search for nutritional solutions that can help support animal health. As such, they can be complementary to the use of vaccines and/or antibiotics. Among them, feeding Optiwall, a yeast cell wall-based postbiotic, developed by Lallemand Animal Nutrition, has emerged as a promising option. Optiwall has a guaranteed composition in β-glucans and mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS) that work synergistically.

Pathogenic E. coli present in the intestinal lumen must first adhere to the intestinal mucosa to initiate the production of the toxins responsible for both local and systemic damage. This adhesion is a critical and necessary step in the infection process. The MOS receptors of Optiwall exhibit high pathogen-binding properties targeting strains commonly found in poultry farms, including E. coli and other pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella spp. The irreversible adhesion of these pathogens to Optiwall’s MOS receptors help reduce their concentration within the gut before they adhere to enterocytes, and ensures their excretion via the feces. This mechanism contributes to limiting bird contamination through inhalation or ingestion. It also helps lower bacterial pressure and spread caused by dust in the poultry environment, as previously illustrated in Figure 4, titled: “Vicious Circle of bird recontamination by E. coli”.

This pathogen-binding capacity has been measured using flow cytometry, a new analytical method developed by the R&D team at Lallemand Animal Nutrition, published and peer-reviewed. Depending on the E. coli strains tested, up to 10–12 bacteria can be durably bound to each Optiwall particle. This binding ability is mainly enabled by the length of the MOS chains present in this specifically selected yeast cell wall.

When added to the feed throughout the poultry production cycles, Optiwall can help reduce the risk of colibacillosis outbreaks in poultry farms. Supplementing birds with this specific yeast cell wall also improves zootechnical performance, as supported by findings from both academic and field trials. The dose can be tailored to farm-specific pathogenic pressure and help maintain animal health.

Optiwall represents a valuable solution to enhance bird resilience and reduce pathogen pressure, ultimately supporting better productivity. By maintaining bird health, the need for antimicrobial interventions is reduced.